Love and Death

General Assembly 2008 Event 3012

Sponsor: Meadville Lombard Theological School

Presenters:

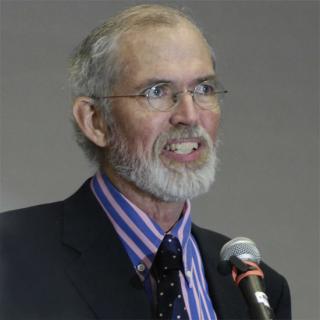

Rev. Dr. Forrest Church, Rev. Dr. Lee Barker

“One of the great things about dying slowly,” Forrest Church reported Friday morning to a capacity crowd in the Fort Lauderdale Convention Center’s Floridian Ballroom, “is that you have an opportunity to punctuate your life’s story and to write a coda. This book is the coda of my theology. It has been a great privilege to be able to write.”

The newly published book, Love and Death: My Journey Through the Valley of the Shadow, begins with the announcement Church made to his congregation (All Souls in New York) on February 4 of this year: He is dying of esophogeal cancer, and his time remaining “is likely to be measured in months, not years.” Similarly, Church did not dance around the subject of his mortality Friday: “This General Assembly is a very special occasion for me. Barring some sort of miraculous but nonetheless unexpected turn in my health, it will be my last opportunity to celebrate with you the gift of our chosen faith.”

His talk, assembled largely from excerpts of the new book (which, in turn, is assembled largely from excerpts from his thirty years of sermons) was indeed a celebration, a valedictory of his theology and worldview, ending in a long standing ovation from the audience.

Death has always been a central theme of Church’s work. In his introductory remarks, Lee Barker of Meadville Lombard Seminary, recalled Church’s famous definition of religion as “our human response to the dual reality of being alive and knowing we must die.” Barker put the challenge clearly: “Now as you can clearly see your own mortality, your religion and your ministry are receiving their truest test.”

Church began by reaffirming his belief that death is a central motivator of religion. “The questions death causes us to ask are at heart religious questions: Where do I come from? Who am I? Where am I going? What is life’s purpose? What does all this signify?” But, he went on to say, “Death is not life’s goal, only life’s terminus. The goal is to live in such a way that our lives will prove worth dying for.” And that leads to his book’s (and his career’s) second theme: “This is where love comes into the picture. The one thing that can’t be taken from us, even by death, is the love we give away before we go.”

He put his illness into perspective by comparing the human outlook on life to a stained-glass window. “Each pane looks out on some aspect of life: our vocation, avocations, our spouse or companion if we have one, our parents, our children, our health.” We often take a pane for granted when it is unproblematic, but when one starts to go dark “the natural human tendency is to press our nose up against that one frame, desperately trying to see through it. When we do this, we lose all sense of proportion; our entire world goes dark. How easily this tendency kicks in when we’re dying…. With our nose pressed up against the one pane we can see nothing through, all our other lights go out. We then invest our life’s remaining meaning in that which may be impossible, namely, beating our sickness. Nothing else matters. … We may so obsess on our sickness that we lose appreciation for all those things in our life that we would dearly pray be returned to us if someone suddenly snatched them away.”

Instead, Church chooses to focus on a mantra he developed before discovering his cancer:

“Do what you can.

Want what you have.

Be who you are.”

“Those who know my mantra sometimes test me with it: ‘So, Forrest, do you really want cancer?’ I reply: ‘I want what I have.’ … We cannot selectively wish away what is wrong with us without including all that is right. … In short, I back away from the darkened pane of my health to gain a prospect of the whole window I am blessed to look through.”

He commented on the intensity that the prospect of death can bring to life: “Much of the time we drift through our days. Life lives us…. Death threats are wake-up calls. No longer able to take life for granted, we seize the day and receive it as a gift.”

“This doesn’t always happen, of course.” Church noted the Kübler-Ross stages of grief and acknowledged that not everyone who faces death completes the stages and arrives at acceptance. From his decades of experience in pastoral counseling, Church has learned to associate non-acceptance with “unfinished business”—those basic life issues and broken relationships that have been put aside for some later time. Sometimes these issues can be resolved quickly at life’s end. “I have witnessed amazing last-minute reconciliations and conversions … that almost miraculously turned the defeat of death into a victory.” But in each case involving substantial unfinished business “when acceptance came, it came hard. And often it did not come.”

Church attributes his own near-immediate acceptance to the spiritual work he began when he stopped drinking eight years ago: “I had conducted a fearless moral inventory, made amends where it was possible and appropriate, recovered my good conscience, made peace with myself, then with others, then with God. If I hadn’t, when this death sentence came, I know that I would have been crippled by regret.”

“Don’t get me wrong. I am not happy about the prospect of dying. I have things left to do in life, and regret the interruption of all my splendid plans. My acceptance, however, abides in a deeper place. I am free to die, I realized some time ago, because although I have much ongoing business, I have no unfinished business.”

“I had more to learn, however. Smugness, which I was teetering on, is not a lofty spiritual perch.” Church’s wife reminded him that his death “is not entirely my own, to do with as I please.” He needed to help his children reach acceptance also, by giving them the opportunity to work out the unfinished business they had with him. “They needed to say things they had not said, show me things about themselves that I had missed, make a deeper connection with me that could sustain them after I was gone.”

“Mere acceptance was too easy,” he realized, “too selfish. The network of relationships that binds us has its own moral demands that we cannot meet on our own, only together.”

The next theme Church discussed was salvation. “Being agnostic about the afterlife, I look for salvation here—not to be saved from life, but to be saved by life, in life, for life.” He postulated three dimensions of such salvation, each of which leads to peace on a different level: integrity, which brings peace with ourselves; reconciliation, bringing peace with others; and finally redemption, which “comes when we make peace with life and death, with Being itself, with God.”

Church urged his listeners to begin this work of salvation now, and not to wait until death is imminent. He described this as “lifework, not deathwork” because its benefits and challenges are not restricted to the moment of death: “To be free to accept death is to be free—period. The courage we need comes before, when we face our own demons, or reach out across a great divide to touch hands. … You know what your unfinished business is. Don’t wait until it’s too late to begin taking care of it. … In taking care of your own unfinished business, and in helping your loved ones take care of theirs, you can liberate yourself and then them from suffering that if you wait too long may one day become intractible.”

Salvation, in Church’s formulation, can never be purely individual. “Whenever a trapdoor springs open or the roof caves in, don’t ask why. Why will get you nowhere. The only question worth asking is where we go from here. And part of the answer must be: together. … Together we do love’s work, and thereby we are saved.”

Finally, Church addressed the human tendency to ask “What did I do to deserve this?” In response, he expanded the notion of “this” to include not just the current disease or misfortune, but life itself. That any of us were born at all, he noted, “hinges upon an almost infinite sequence of perfect accidents.” He illustrated this sequence by recounting the survival of his ancestor, John Howland, who was rescued in the mid-Atlantic after falling off the Mayflower. “Had John Howland drowned,” Church joked, “you might be hearing a better speech this morning, but I most assuredly would not be delivering it.”

He urged humility in the face of this miracle of life, and encouraged his listeners to awaken to it. “Awakening is like returning after a long journey and seeing the world, our loved ones, cherished possessions, and the tasks that are ours to perform with new eyes. … We may not understand any better who we are or why we are here, but for this fleeting moment, this one instant we can bank on, our life becomes a sacrament of praise.” Whether or not this awakening will lead to a “dance in the ring of Eternity” Church would only say “Who knows?” But “we will join the dance of life with more exuberance. How much finer it will be when our band is struck, if we have loved the music while it lasted. Enjoy the dance.”

After a long and warm ovation, Barker returned to the microphone with this comment: “Generations from now, scholars and ministers will pose the question: What made Forrest Church such a towering figure in the late 20th and early 21st centuries on the religious landscape. All they will need to do is to plug in the video screen and watch what happened during this last half hour.”

Reported by Doug Muder; edited by Jone Johnson Lewis.

The Unitarian Universalist Association and All Souls Unitarian Church in New York City have partnered to establish the Forrest Church Fund (FCF) for the Advancement of Liberal Religion, a tribute to the most influential Unitarian Universalist minister of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries.