UUs and the Battle for Christmas

By Gail Forsyth-Vail

Many of us like to point out our UU connections with well-loved Christmas music and rituals. Charles Follen introduced the first Christmas tree in the United States. Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women sacrifice their own Christmas presents for impoverished neighbor children. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol celebrates the virtues of hearth, generosity and merrymaking. “Jingle Bells,” “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear,” and “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day”—all composed by Unitarians.

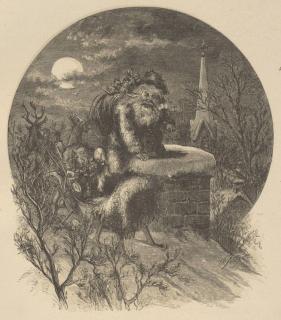

When I picked up a marvelous, and very readable, social history book, The Battle for Christmas, by Stephen Nissenbaum (Random House, 1996), I learned “the rest of the story.” Nissenbaum takes us back through U.S. social history, to a time when Christmas was an occasion for revelry and misrule, when Christmas carols were drinking songs, when people in lower social classes ritually invaded the homes of their wealthy patrons to receive food, drink, and presents in exchange for goodwill. He explains how as the economic class divide deepened in an industrializing economy, wealthier people harbored both fear of the lower classes rioting and guilt about the conditions under which poor people lived.

Nissenbaum shows us the Universalists were among the first to embrace Christmas as a religious holiday, holding a Christmas service in Boston in 1789. The Unitarians were calling for public Christmas observances by 1800, hoping to temper the general rowdiness of the season. Episcopalian Clement Clarke Moore’s myth-creating masterpiece, A Visit from St. Nicholas, published in 1822, deliberately domesticated Christmas.

Modern Christmas traditions, centered on children, gift exchange and charitable giving, were born in the decades that followed; our UU religious forbears were among those who created Christmas as we know it. The growth of the family Christmas celebration, a “festival of feelings,” went hand-in-glove with the liberal religious embrace of childhood as a time to receive guidance and protection. Charity, given to strangers, became differentiated from presents, given to loved ones, and both became obligatory parts of the holiday. Romanticized notions about poverty helped assuage guilt among charitable givers. Painters portrayed deserving recipients—meek, uncomplaining, grateful and sometimes disabled. Children such as Tiny Tim perfectly filled the bill.

In The Battle for Christmas, I found threads of our heritage that are still with us today, some worth celebrating and others more challenging. The growth and development of middle class consciousness in Unitarianism and Universalism co-existed with our impulse to lift up those on the margins. A commitment to progressive education and to families is reflected in our love of Christmas… as is a tendency to romanticize or judge recipients of charitable giving and service. There is much to think about and share in The Battle for Christmas.

Next Steps!

Have you wondered who brought the Christmas tree inside the house? Read “Charles Follen’s Christmas Tree” online in the Winter 2013 UU World.

Find a diverse array of Christmas readings, prayers, stories and other resources in the UUA’s online Worship Web.