Asking for Refuge

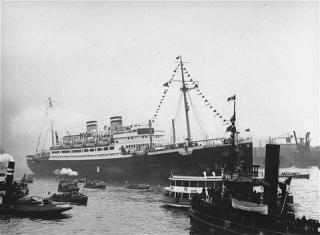

The MS St. Louis in port in Hamburg, Germany

In eighth grade, we were assigned a project: to make a poster about some part of our ancestry. I made mine about the story of the 1930 migration, from Germany to the United States, of my great-grandmother, her husband, and their three children.

My great-grandmother, Emma Johanna Jacoba Kranenburg Mehl; her husband Carl; and their children, Irmelin, Fritz, and Ingrid, sailed for New York and made their way by train to Washington state. Carl had fought in the first World War for the Kaiser, and Carl saw the signs: he knew by 1930 that another war was coming. So they sold the house and vineyard and left Europe behind.

For my eighth grade poster, I assembled family pictures of New York in 1930, a map of the route, and a photo of the ship they sailed on: the MS St. Louis.

I quote to you an official version of the story:

On May 13, 1939, the German transatlantic liner St. Louis sailed from Hamburg, Germany, for Havana, Cuba. On the voyage were 937 passengers. Almost all were Jews fleeing from the Third Reich. Most were German citizens, some were from eastern Europe, and a few were officially “stateless.” The majority of the Jewish passengers had applied for US visas, and had planned to stay in Cuba only until they could enter the United States.

The drama of the arrival in Cuba was complicated; most of them were denied entry. Negations to secure their entry were unsuccessful: the new Cuban president had supported Franco who had been supported by Hitler, and he wanted a bribe that the refugees were unable to pay.

Again, the official account:

Hostility toward immigrants fueled both antisemitism and xenophobia. Both agents of Nazi Germany and indigenous right-wing movements hyped the immigrant issue in their publications and demonstrations, claiming that incoming Jews were Communists.

Reports about the impending voyage fueled a large antisemitic demonstration in Havana on May 8, five days before the St. Louis sailed from Hamburg. The rally, the largest antisemitic demonstration in Cuban history, had been sponsored by Grau San Martin, a former Cuban president. Grau spokesman Primitivo Rodriguez urged Cubans to “fight the Jews until the last one is driven out.”

A few passengers were accepted, but 743 were not. They went north. “Sailing so close to Florida that they could see the lights of Miami, some passengers on the St. Louis cabled President Franklin D. Roosevelt asking for refuge. Roosevelt never responded. The State Department and the White House had decided not to take extraordinary measures to permit the refugees to enter the United States. Public opinion in the United States, although ostensibly sympathetic to the plight of refugees and critical of Hitler’s policies, continued to favor immigration restrictions. Roosevelt was not alone in his reluctance to challenge the mood of the nation on the immigration issue. Three months before the St. Louis sailed, Congressional leaders in both US houses allowed to die in committee a bill [that] would have admitted 20,000 Jewish children from Germany above the existing quota.”

The ship was turned away.

The official account, from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, concludes as follows:

“Following the US government’s refusal to permit the passengers to disembark, the St. Louis sailed back to Europe on June 6, 1939. Jewish organizations negotiated with four European governments to secure entry visas for the passengers: Great Britain took 288; the Netherlands admitted 181, Belgium took in 214; and 224 found at least temporary refuge in France. Of the 288 passengers admitted by Great Britain, all survived World War II save one, who was killed during an air raid in 1940. Of the 620 passengers who returned to the continent, 87 managed to emigrate before the German invasion of Western Europe in May 1940. 532 St. Louis passengers were trapped when Germany conquered Western Europe. Just over half, 278 survived the Holocaust.” The rest, 254 souls, were murdered.

Every time I read this account, I weep.

I weep. Because my family got on the boat, and got off. And took the train.

And so I live.

Every time I read this account, I weep. I don’t know what else to say.

I want to take every politician and pundit — everyone whose heart has shrunk two sizes too small — and sit down at a table together. A kitchen table, perhaps, where we sing with joy, with sorrow. We pray of suffering and remorse. We give thanks.

A kitchen table, and we can pray, give thanks, and recall our ancestors; I’ll read the account of the St. Louis and its passengers, and I’ll read it again,

and I’ll read it again,

and I’ll read it again,

until their hearts are opened and their conscience awakes.

| Date added | |

|---|---|

| Tagged as |