Noah: A Sticky Story

By Gail Forsyth-Vail

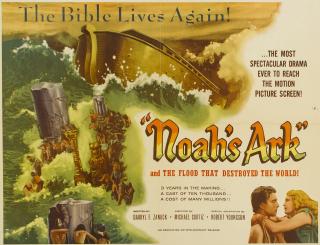

Storytellers make choices all the time. We choose which parts of a story to lift up and which to downplay or omit; which characters to develop, and how; and which dilemmas to emphasize. This is especially true when it comes to stories from the Bible. It was so with the great biblical films and dramas of my growing-up years, and so it is with Darren Aranofsky’s recent epic, Noah.

When I was growing up, Bible movies dominated the television screen during the Christian Holy Week and the Jewish Passover week. We saw Charlton Heston play Moses in the 1956 film, The Ten Commandments. We watched Barabbas (1961), which depicts the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus and the persecution of early Christians. There were The Robe (1953), Ben-Hur (1959) and others. Made during the Cold War years, these films reflected the sensibilities of the time; the films clearly showed what (and who) was good and what was evil by adding dramatic details and expanding on the stories told in the original text. Despite the best attempts of my Sunday School teachers to convey what was written in the Bible, for a long time I understood the Passover story through Heston’s portrayal and Jesus’s last week through the eyes of fictional early Christians. Those stories were sticky. They became part of my religious formation, not to be dislodged until Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell came along.

I recently watched Darren Aronofsky’s Noah. I think we need to take the film seriously, and to talk about it with older children and youth in our families and congregations. Like the epic Bible movies of old, it is likely to be sticky. It is a direct challenge to the nursery tales of cute, two-by-two animals and all the folklore about who did and did not make it onto Noah’s ark. It engages questions like the tension between justice and mercy, and whether or not human beings are so flawed—so sinful—that we are a threat to creation itself. While depicting the utter destruction of humanity and other living creatures, it asks, “Are humans worth saving?” Theological questions worth asking.

At the same time, the film uses an all-white cast, a choice that seems a serious flaw, especially when dealing with this story. In the nineteenth century, extrapolations from the Noah text provided one of the biblical justifications for chattel slavery. In the text, Noah curses his son Ham, saying, “a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.” Apologists for slavery made their own story choices: In their telling, descendants of the cursed Ham became the African race, rightfully destined to be enslaved to white people.

When I was a new DRE, we used a UUA curriculum called Focus on Noah (published in 1974). As I recall, the curriculum explored archeology, Near Eastern mythology, and biblical scholarship as they related to the Noah story. It was good for understanding how this part of the Bible came to be written, but did not engage the theological content of the story.

This new Noah presents not only an opportunity but, arguably, an obligation as religious educators to engage in the theological content with older children, youth, and adults. Because this film will become part of the way our culture understands the story of Noah, we need to talk about it. We need to talk about the all-white cast and why that is a problem. We can recount the use of this story in justifying enslavement of Africans in the United States. We can examine the theological questions inherent in the film, and ask ourselves why we have turned a story about utter destruction into a suitable subject for nursery décor. We can use the film as a vehicle for engaging a complex story and figuring out what, if anything, the biblical story of Noah might say to us today.