History Vignette 20: Liberal Religion on the Norwegian-American Frontier

By Nora Church UU, Hanska, MN, Victor Urbanowicz

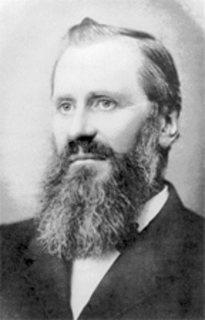

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson

(Regarding authorship, see the Editor’s Note at the end.)

The settlers around Hanska, Minnesota, came from the area of Toten and the valley of Gubrandsdal in Norway during the 1860s and ‘70s. They found many hardships in this raw new land, but the stamina of many years of struggle in Norway stood them in good stead. As was expected, they formed Norwegian Lutheran churches, and the churches were the center of the community, both religiously and socially, and the pastors the leaders who held the rural people together.

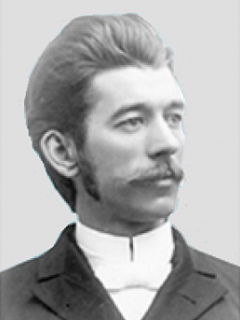

Henrik Ibsen

It is said that the people who started Nora church in Hanska broke away from the Lake Hanska Lutheran church in 1881 because they could no longer tolerate the bitter dissension that characterized congregational meetings. Several issues were at stake, including the question of who could be buried in the church cemetery. But there is more to it than that. Many of the people had been influenced even in Norway by liberal reformers such as the poet Henrik Wergeland, Henrik Ibsen, and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson—men who were speaking against the absolutism in the Norwegian church.

A Cultural Luminary of Norway Becomes a Unitarian Missionary

Kristofer Janson

In 1879, a good friend of Ibsen and Bjørnson, the noted author Kristofer Janson, poet laureate of Norway, came to America for a lecture tour. He was well received among the Norwegian community, and he gave popular talks on the use of the peasant language Landsmaal, for which he had been a successful advocate in Norway. He also spoke on social and political topics and interpretations of Norse folk tales. Toward the end of his tour, he began to speak out against the Norwegian Lutherans — the dissension among the five rival synods, the church’s defense of slavery, its opposition to the common school, its rigid fundamentalism, and its policy of keeping parishioners cut off from American society. These lectures were called heresy, and the Norwegian press, previously in love with everything he did, now considered him the worst of rogues.

While in America, Janson became acquainted with several Unitarian ministers and found in Unitarianism the kind of free religion he was seeking. After his return to Norway, both he and the school which employed him realized that his religious views had become too liberal for him to remain in his position. So he applied to come to America as a missionary Unitarian minister among the Norwegian immigrants, and was accepted.

They Had Long Been Unitarians Without Knowing It

In 1879 Janson lectured in Madelia on peasant reform in Norway, and the audience was enthralled. In that audience were several people from Hanska, some of whom had walked the eight miles to hear Janson. Among these were members of the group that had broken away from the Lake Hanska church and founded their own independent congregation, which they called Nora, after one of the three maidens symbolizing Norway, Sweden and Denmark—Nora, Svea and Dania. Nora simply means Norwegian. They organized in August, 1881, and by December had still not found a Lutheran minister willing to serve them. Then they remembered Janson and his message, and heard that he was now a Unitarian minister in Minneapolis. They did not know what to make of Unitarianism, but they wrote Janson, sending their constitution, and asked him to become their minister. Janson agreed to meet with the group, telling them frankly that his preaching was not what they were accustomed to:

I told them openly and honestly that I did not agree with the gospel that they were used to, and why I believed as I did.

But to judge by the looks on their faces, they thought it was pretty funny. They looked around at each other, and one simply could not keep from smiling and nudging his neighbour with his elbow. Finally, it was as if a liberating sigh went through the entire congregation, and one or another of the bravest members confided in me that secretly, deep inside, he had thought the same as I, but he had simply not dared to say it out loud.

They readily put aside the old idolatry with Bible texts, the contradictory trinitarian dogma, the bloody teachings about atonement and eternal Hell. The hardest part was giving up their faith in Jesus as a god, but I reassured them with the thought that … what we should agree about is to love Jesus and follow him. Then our opinion as to whether he was a god is a little detail that should not divide us.

Janson agreed to be their minister, although he could only be here in the summers and preach eight times a year. By February there were forty voting members, including women, who from the beginning had equal rights in every way.

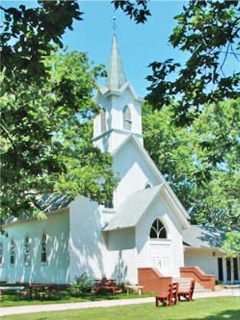

Church with Summer Cottage

The first church was built on the top of the hill where the members had bought land to establish a cemetery, but on the Saturday before the first service was to be held, as Janson and others were putting the finishing touches on the new building, a tornado came and destroyed the church, scattering some sixteen people down the hill, but hurting no one seriously. The local Lutherans declared that God had spoken against the heresy of these liberals, even though the same tornado also put the Lake Hanska church askew on its foundation.

The church was soon rebuilt with the aid of Unitarians in the East. The new building (right) was put a bit down the hill, and still stands. Then a summer cottage for Janson and his family was built. On the day the new church was dedicated, Janson stood on top of Mount Pisquah (the high point of the land around the church, so named by Catholic missionaries) in his long Prince Albert coat and raised the Norwegian flag. Teams of wagons came from all directions, until the congregation numbered about 400.

Over the years, the congregation was bitterly assailed, not only by its neighbors, but in the Norwegian press. At one point the president, Johannes Mo, wrote pleading that Norwegians in America live and let live. They were barraged with slander and abuse from every side, even from the local pulpits.[1] It was extremely difficult for these liberal pioneers, for they no longer had the support of the Norwegian church and all the tradition that went with that, or of a resident pastor to lead them and care for their needs. Although they carried on services and social events during the winter, baptisms, confirmation classes and the like had to wait until Janson came in the summer. It was very lonely. People who had come from the same town in Norway and been friends for years no longer spoke to the Unitarians. All of the support provided by the Norwegian church to the immigrants was unavailable to the members of Nora church.

Still, the church thrived. The people were sustained by their religion, the pride they had in their new church, and the inspiring words of their minister. Kristofer Janson wrote many of his best novels and poems while here on the hill. He served as minister until his return to Norway in 1893, when a protégé of his, Dr. Amandus Norman (left, 1893 photo) took over both his church in Minneapolis and the one in Hanska, on the same basis.

[1] Nina Draxten, Janson’s biographer, takes note of opposition to Janson’s liberalism by the local Norwegian-American Lutheran clergy and suggests that they could have crushed his missionary efforts except that they were too occupied with theological disputes among themselves! –V.U.

Nora UU Victorian Parsonage

The Minneapolis church did not succeed, and when it closed in 1906, Norman came to Hanska full time, and a lovely Victorian parsonage (right) was built for him and his family. He stayed until he died here in 1931.

But it is amazing that this small rural church survived, not only the first 25 years when it had no permanent resident minister, but the later years when most other rural Unitarian churches in the Midwest died. Think of the dedication those early Norwegian liberals must have had, in the face of the abuse and hatred they endured, alone in their beliefs among their countryfolk, yet steadfast in their determination to worship as they felt right.

Contributions to Hanska

Hanska Community Center

Historically, then, this church is very important. Like the Unitarian Church of Underwood, Minnesota, which also was founded by Kristofer Janson and supported by Amandus Norman, it is unusual for being a surviving rural congregation founded by Norwegian immigrants. In addition, the Hanska congregation has contributed a great deal to both the local community and the denomination over the years. The Hanska Community Center (right), for example, was built by this church in 1910 as a place where people could meet and socialize, dance, and put on plays and musicales and stay out of the bars, and where they could hear secular, educational and political speeches. It also housed the first library, again started by members of this church. Nora church has been, and continues to be, a bright beacon on the prairie.

Nora Church UU today

Being a rural church, however, it suffers from the same forces that have assailed many small farm communities. The population around the area has decreased, and now the church draws from a hundred-mile radius for its 70 members. It is, however, still a vital liberal presence on the prairie, proud of its heritage, and firmly committed to its future. The grounds, church, cemetery, log cabin museum of immigrant artifacts and the parsonage are well-kept and beautiful. For many it is a sacred place.

For more history on the different names the church has used, please read What’s in a Name?, by the Rev. Lisa Doege, Minister of Nora Church.

Editor’s Note: This history was a joint effort by several of the congregation’s members. I agree with Reverend Lisa Doege and the congregation’s president, Jeanie Hinsman, that it is best not to identify any contributors until all can be identified, this being a task best left to the membership. It would be gratifying to identify individuals who wrote so well. The few changes I made were adjustments for audience and one factual matter. I also inserted Janson’s anecdote under the heading “They Had Long Been Unitarians Without Knowing It.” The church’s version contains a link to the story, but it seemed well worth adding to the main text. — Victor Urbanowicz

Related Reading

Draxten, Nina. Kristofer Janson in America. Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1976.

Jonasson, Stefan. “Nordic Strands of Our Living Tradition.” UU World, 2/21/2011.