Tracing the Origins of Racism

By Seble Alemu

Unitarian Universalists have a long history of engaging in racial justice advocacy individually and as congregations. As people of faith who believe in the inherent worth of every person, UUs strive for justice, equity and compassion in relationships and work for systemic change through advocacy.

At the end of May, I attended an event called “Understanding the Origins of Racism, Afrophobia & Colorism and the Movement for Reparations.” Hosted at Baha’i Center and organized by the United Nations NGO Committee for the Elimination of Racism, Afrophobia and Colorism (CERAC), this event was part of the International Decade for People of African Descent 2015-2024 event series.

Manbo Dowoti Desir, Chairperson of CERAC

Founded in 2000, CERAC grew from Subcommittee for the Elimination of Racism status in the NGO committee for Human Rights at the United Nations. As the standalone committee it is now, CERAC takes bold stance against the invisible respect, insufficient recognition, and grievous injustices that people of African descent face globally through advocacy, development of global policy and dissemination of educational information. The UU-UNO’s Director Bruce Knotts once served as co-chair of the subcommittee.

There are many shared values between Unitarian Universalists’ social justice ideals and CERAC’s mission and vision. Both are dedicated to ending racial discrimination and injustice holistically: starting within ourselves and moving out into the world around them. Aware of the renewed attention and energy toward racial justice work in recent years, UUs and CERAC take steps putting faith in action, engaging at the grassroots level fostering collaboration to learn, grow and celebrate multi-ethnic and multicultural communities. Through advocacy, education and activism the Unitarian Universalist Association and CERAC are making progress in breaking down divisions, healing isolation and promoting the interconnectedness of all justice issues.

A similar deep and multidimensional approach to social justice was reflected CERAC’s event — as the origin of racial intolerance and social control in the United States was traced through economic, social and political analysis. Of course this event would not have been what it was without the intelligent and inspiring speakers: Dr. Jeffery B. Perry, Dr. Bilan Bashi Treiler and Dr. Kwasi Konadu, and the attentively engaged audience. Presenters related theoretical and objective substance on the invention of the white race and white supremacy as well as ‘the ethnic projects’ that racism survives and thrives on. They followed the footprints of racial identification based on skin color all the way back to the 8th Century CE, and the origins the reparations movement back to the Belinda petition to the Massachusetts court in 1783.

Takeaway Lessons

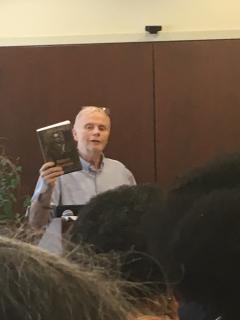

Dr. Jeffery Perry

The take away from Dr. Perry’s talk was that race is beyond a social construct. It is invented for the purpose of making profit and maintaining social control against the interest of Blacks and working class Europeans. Because race and class are intertwined to sustain white supremacy, efforts taken to revive economic crisis such as the Great Depression actually set back the economic progress of blacks. For example the New Deal, which was nationwide economic relief, recovery and reform tactic, did not work in favor of People of Color. The black to white unemployment ratio that was 1:1 in 1929 was 2:1 by the end of the New Deal. The connection between racial and economic justice is inextricably linked in all aspects of society, a relationship addressed in the UU-UNO’s 2016 Intergenerational Spring Seminar.

On the other hand, politically People of Color are “the touchstone” of all contemporary human rights struggles in the United States. Blacks’ struggle for rights and dignity led to the suffragist efforts, the labor movement, and even the LGBTQ rights advocacy. Dr. Perry’s presentation concluded insisting that white supremacy is historically a principal retardant to social change efforts, and that struggle against white supremacy should be central to efforts against racism. Racism is always an obstacle to creating fair and loving communities.

Dr. Vilna Treitler

Building off the topic of white supremacy, Dr. Treitler introduced the concept of “ethnic projects,” in which racism survives and thrives in the United States. The term “ethnic projects” refers to the racialization of new migrants — an iterative incorporation process guided by white supremacy. This phenomenon can be best understood with clothing and drawer analogy. If the racial hierarchy is bureau, the racial categories are the drawers, and ethnicities are found inside.

The history of America can be summarized by various migrants groups’ struggles to leave the bottom drawer without disrupting white supremacy, which is the top drawer. Once new groups learn the language, the practice of the race and the struggle against their own position — they exert pressure to change the paradigm in which they participate. At the bottom drawer there are large numbers of African Americans systematically barred from leaving while various immigrant groups i.e. the Italian, the Irish, and the Chinese became “white.” Racialization is legitimized by a racial paradigm that is made of categories and hierarchy, as well as racial “commonsense” and racial sanctions. The ethic projects are a racialization cycle that sustain racism and allow intolerance to thrive.

Dr. Kwasi Konadu

Getting the story on the origins of racism correct is particularly important when considering reparations. Dr. Konadu advised that reparation is an idea we have to prepare for in constructing what would satisfy and benefit people of African descent, but also build infrastructure and modes of delivering the amends. Historically, requests for reparations have been proposed at the government, courts, and civic groups in the form of economic benefit/monetary gains for blacks. The first request for reparation was granted to Belinda by the State of Massachusetts; Belinda was an eighty-year-old slave whose owner passed away. The Pension Movement led by Isaiah Dickerson and Callie House was successful in petitioning Congress and providing tax reliefs and monetary assistance to ex-slaves. In 1969 James Forman demanded reparations from white churches and synagogues government and won three million dollars, which he put towards education.

Reparations can vary from verbal apologies or tangible benefits. Although in the past reparation was defined by monetary compensations, reparations can be done per each sector of society: health, education, housing etc. The conclusion about reparations is unclear, as the concept of reparation itself, reflecting the need for further discussion of the topic.

Attendees of the event engaged in Q&A

My main take away from this event is that as individuals, as society, and congregations we have to constantly engage ourselves in learning about the realities of racial inequality and injustice. As Unitarian Universalists define their social justice legacy as a policy of “deeds not creeds,” we have to connect with, embrace, and support social justice movements through contributions of our money, skills, time and more. I am convinced that doing so will empower and grow our love and belief in the inherent worth of every person, which are fundamental gears to harness to stop oppression against people of African decent and all others.