Time for Thinking Like an Ancestor

By Joe Sullivan

Many are eager to move beyond the past year. It’s hard to find fault with that. Spring has arrived along with ramped up distributions of COVID vaccines. We can’t help but leap to reclaim our lost past for a new future.

Ever anxious to move forward, we find ourselves in acute tension between an insatiable desire for a new normal beyond the pandemic and restorative nostalgia for a “before” time based on memories of the ways things were 13 months and more ago. In practical terms for congregational leaders, this tension presents as fixations on return to church buildings and Sunday experiences that capture memories of pre-pandemic ways as well as new accessibilities and innovations acquired over the past year. Understandably, we find ourselves confused, struggling over how to move with surety into a desired new normal that incorporates before-times memories and new learned qualities.

Wisely, many faith leaders, writers, and activists have offered a more reflective third dimension between the tensions of before-times nostalgia and new world futures. They invite us to seek and reflect on insights and lessons wrought from a year of altered time.

Noticing that a number of ministers would be preaching on March 14th about the one year anniversary of their congregations moving to virtual church, I viewed three different services that day. I wanted to hear where these ministers went with their reflections. To what direction of time would they speak? What lessons from our faith and dimensions of ministry would they would offer? I was grateful none focused on before-times. Neither did they attempt to paint a rosy future. Instead, they offered messages of pastoral ministry and invited reflections of this past year through rich and ancient lessons of loss, grief, disorientation, resilience, interdependence, service, creativity.

Similarly, some secular voices have cautioned against nostalgic yearnings, named persistent inequitable realities, and offered liberating lessons from the past year worthy for our reflection. One such offering is a recent series of opinion articles from the New York Times titled “The Week Our Reality Broke” reflecting on how the year of living with the coronavirus pandemic has affected American society. In her piece in the series “The Past Year Has Taught Me a Lot About Nostalgia” essayist and novelist Leslie Jamison writes how the vein of nostalgia clouding our present yearnings is grounded in delusion—incomplete, unreliable, biased. Jamison describes our nostalgia as “a sneaky curator”, one that often neglects how the before times were really not so hunky dory for many marginalized communities. The past year of pandemic has not been experienced equally.

This last point is brought home in stark statistics by Yaryna Serkez in her piece “We Did Not Suffer Equally.” She shows that the pandemic worsened already entrenched disparities—in unemployment, education, housing, health and even survival—and highlights how our experience of the pandemic has been far more based on our position on the socioeconomic spectrum than on luck or fortune.

Nostalgic thinking that seeks to restore some form of “normal” can be unfaithful to our values as Unitarian Universalists—aiming far too low when the world needs people of faith to bring the fullness of their good news in service of building a better world.

Jamison does suggest a form of beneficial before-times thinking—reflective nostalgia—and points to mutual aid groups as examples of what it might look like. She describes reflective nostalgia as thinking that “interrogates the very image it longs for” to remake rather than restore past conditions. In “Our Year of Mutual Aid”, another article in the NYT series, Maira Khwaja and other organizers in Chicago describe “the constellation of mutual aid groups that have emerged across Chicago, and the country, since the pandemic began” responding to needs to look out for one another. Mutual aid groups have a storied tradition within marginalized communities—communities used to being underserved by official public institutions. As the authors state “if our public institutions wouldn’t provide, we would.”

From these sources within and beyond our faith, I hear caution about urgency to plan some return to a lost normalcy. I feel instead the call to the Practices of Spiritual Leadership, specifically the practice of *Binding to Tradition. When we claim Unitarian Universalism as a religion, we bind ourselves to something that puts an obligation on us. We claim it and it claims us back. One obligation involves building on the gifts and wisdom of our UU tradition and carrying them forward toward what is yet to come.

*Binding to tradition invites us to think and act like future ancestors. To examine past and present experiences and conditions for how we saw the theological values and teachings of Unitarian Universalism inspiring and guiding our actions. Conditions of this past year have offered an unrelenting supply of experiences for faith communities to respond to.

What if instead of jumping right into decisions and plans for worship experiences following lifting of pandemic restrictions, we tarry in reflection on the conditions we and those around us in the wider community have experienced over the past year and before, and how we as individual UUs and UU congregations responded? What if we asked how this past year has shaped our congregation’s sense of purpose? What if our next actions were made with an assurance that descendants will be reading and learning about this time—looking for and asking questions about how we lived and shaped this faith in light of this time?

In their NY Times article on mutual aid groups, Khwaja and co-authors state that their projects offer “glimpses of a society where we meet one another’s needs.” Likewise activist Mariame Kaba described mutual aid as a way of “prefiguring the world in which you want to live” (The New Yorker, May 11, 2020). I like to think that those they are talking about include Unitarian Universalists and other faith communities rising up together and bringing forth the gifts of their traditions in service of collective liberation and the building of beloved communities. May it be so.

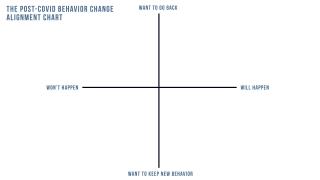

Here is a helpful chart to begin discernment on post-Covid behaviors and expectations:

via Hank Green: "How Will Post Pandemic Behavior Change?" (YouTube)

Subscribe to receive our blog posts directly to your email!

* We have recently changed the name of this practice to Tending Our Tradition, in recognition that the metaphor of binding may have a charge that is harmful for Black people, people of Asian descent, and others.