Women's Rights and Freedom of Religion

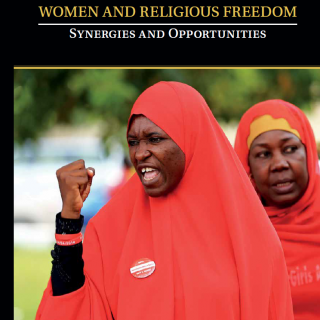

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom released a report in July 2017 entitled "Women and Religious Freedom: Synergies and Opportunities" - by Professor Nazila Ghanea, Associate Professor in International Human Rights Law at the University of Oxford.

After the initial passing of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) at the United Nations in 1981, many states declared ‘reservations.’ These reservations related to implementing the document's provisions in their respective states on the grounds that they violated the states' and communities' rights to Freedom of Religion or Belief (FORB). Among these nations were the People's Republic of Algeria, which claimed reservations on Articles 2 and 16 (PDF) in the case that they “should contradict the provisions of the Algerian Family Code.” Various others including Egypt, India, Saudi Arabia and Ireland had similar reservations. Just recently in the United States, the Trump administration issued rules that carve exceptions into the Affordable Care Act provisions that required insurers and employers to provide contraceptive coverage for women. The rules essentially open up the range in which insurers and employers can refuse to provide this coverage under the grounds that it conflicts with their religious or moral beliefs. This too accentuates a perceived contention between FORB and women's rights.

Where does this perceived contention derive from?

Even in the initial stages of addressing this issue, the most prominent concern seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding of the rights afforded by FORB. A 2013 report (PDF) from the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief explained that FORB “does not protect religions per se (e.g., traditions, values, identities, and truth claims) but aims at the empowerment of human beings, as individuals and in community with others.” FORB, like any other right, is a human right granted to the individual that in no way protects or provides immunity to religious institutions, laws, or even states. So, in essence, the religious reservations that Member States employ in response to the passing of documents like CEDAW are in fact a misuse of the right, and States must be called out on this use of cultural or religious relativism to evade their responsibilities to protect the human rights of its citizens, including those of women.As the Special Rapporteur on FORB states (PDF):

Prima facie, it seems plausible to assume that freedom of religion or belief protects religious or belief-related traditions, practices, and identities, since this is what the title of the right appears to suggest. This assumption, however, is misleading, because in line with the human rights approach in general, and article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in particular, freedom of religion or belief always protects human beings in their freedom and equality in dignity and rights. To cite the frequently used short formula, freedom of religion or belief protects the ‘believers rather than beliefs.’

The vessel of the right is the individual that holds, professes, and develops religion freely. In this context, FORB does not recognize doctrines, truth claims, practices, and value systems independently, but only in relation to the individual holder. Thus Member States must be discouraged from misusing the right that is FORB which does not in fact grant them the capability to make these reservations.

The inherent antagonism between the right to freedom of religion or belief and the right to women’s equality derives in part from the fact that the sources which grant the two rights were formed from distinct lobbying and constituencies, and disregard one another. Human rights doctrines, conventions, and treaties that hold up the right to FORB generally do not mention women’s rights. A July 2017 study from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (PDF) observed that those “normative standards upholding FORB,” including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (PDF), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (PDF), and the 1981 Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief, “make no mention of women’s equality or even of non-discrimination by sex.” The same is true vice versa: “the main legal source dedicated to the advancement of women’s equality is CEDAW - an extensive 30-article binding treaty. It makes no mention at all of the FORB or indeed of religion. It does not even contain a standard non-discrimination provision calling for no discrimination based on religion or another status.” Generally speaking, the two seem to take insufficient account of one another, which can lead to the perception of them as contesting rights. Another aspect of this is the common misuse of religion as a grounds for the violation of women’s rights: “the invocation of religion may well be covering a range of socioeconomic, traditional, political, and other objectives for states and have a tenuous relationship with ‘religion’ as such.” This becomes a difficult distinction to make, as it requires the analysis of religion and culture, which are often deeply embedded within one another, but it is a crucial element in defining what can and cannot be justified using religion. Distinguishing between religion and culture has become a crucial methodological instrument for reformers, including feminists within various groups who are attempting to redefine the boundaries of religion and culture. Women right can be empowered through distinguishing the elements of religion from those of traditional norms. Not all assertions of FORB can be accepted as manifestation of religion or belief. This does not alter the gravity of these violations, but it does provide insight into the fact of harmful practices including genital mutilation, forced marriage, and honor killings. While these destructive practices are carried out in the name of religion, they are usually points of considerable controversy even in the religious traditions that are used to justify them.

What effects does this antagonism have?

Not only is this antagonism between FORB and women’s rights widely exaggerated due to a misunderstanding of the rights themselves and the proclamations of religion versus culture, but this hostility can also be extremely harmful to the very people that the two sides are attempting to protect. It has the effect of virtually forcing women to choose between elements of their identities; they can enjoy either freedom of religion or equality as a woman, but not both. This is especially true for women of religious minorities, many of whom “suffer from multiple or intersectional discrimination or other forms of human rights violations on the grounds of both their gender and their religion or belief.” While it cannot be denied that various violations of women’s rights can be attributed to religion, this should not undermine the idea that women too have the right to freedom of religion. And when these two rights are seen merely as two clashing concepts, one of which must extinguish the other, there exists a dangerous notion that what is essentially a vital part of many women’s lives will become something that is neither acknowledged, protected, nor fulfilled. In fact, this antagonism can be counterproductive, as the denial of religious freedom has been seen in various nations to contribute to gender inequality. “When respect for the diversity of religious beliefs and practices disappears, gender equality suffers.” (World Economic Forum)

Even in a much broader sense, this understanding of FORB and women’s rights as rights that essentially counteract one another is harmful to the universal concept of human rights as a whole.

What is the actual meaning of FORB and what are its implications?

So what does the right of FORB guarantee and where does its actual definition stand in regards to women’s rights? When understood as a right like any other it is assumed that it is not a right of ‘religion’ in the abstract concept but rather the individual’s right to hold that religion within themselves. The true definition of freedom of religion or belief is the right of “ the individual to understand, interpret, and manifest their religion in harmony with respecting the dignity, integrity, and free volition of others.” (U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (PDF) In this sense, it should not be seen in opposition to women’s rights but rather a potentially mobilizing force against state endorsements and laws that force religious beliefs and traditions upon women, especially when these traditions are discriminatory, oppressive, and harmful. It grants women the right to develop their own beliefs and traditions, in the protection from others.

The freedom of religion in conjunction with the freedom of speech would, in fact, open up religions to questions, debate, and reform. It would allow all to have a voice, from conservative believers to feminists to reformers. By empowering those that are often discriminated against, namely women and girls, religious freedom can be used as shooting off point to question patriarchal tendencies within religious traditions and institutions.

Across the international community there exist examples of individuals and groups that use FORB as a tool for women’s rights and equality often coupled with innovative interpretations of religious texts and traditions. These kinds of groups, such as the Association for Women's Rights in Development (PDF),provide inspiring examples of where synergies between women’s rights and freedom of religion or belief can exist. If this interpretational misunderstanding of FORB is still unconvincing, then it should be understood that legally FORB itself does not protect or give immunity to harmful practices. International policies relating to human rights generally are clear that the use of one right cannot be utilized to violate another, nor can assertions of one person or group of individuals be a legitimate basis for the elimination of the rights of others.

Freedom of religion does not protect religious traditions from challenge and criticism; it recognizes the right to believe or not to believe, to change one's religion and to speak and act on these beliefs. In turn, this means that in fact religious freedom in tandem with the freedom of speech protects and empowers women to make their own choices, and if they so choose, to challenge and reform existing religious traditions and practices that they find oppressive and harmful to their basic human rights. In this sense freedom or religion or belief is, in fact, an essential and mobilizing force for their realization of women's rights. Eventually what it constitutes is room for religious traditions to evolve and change over time.